The Seagull

About this Evening

Unhappy love and freedom in art – are these the central subjects of The Seagull? In Chekhov’s drama, two generations of artists meet in a country house by the lake and argue about art, life and the world. The young writer Kostja wants to change the theatre, but his mother Arkadina refuses to give him recognition and support. But while mother and son and their lovers seem to be irreconcilably opposed to each other, they are similar in their desire for intensity and their cold view of the other generation.

Director Christopher Rüping bids farewell to Zurich with this production. However, his Seagull is not a call for a theatre revolution, but an assessment of the current situation. After all, the play also addresses this: the precise measurement of one’s own position, the question of one’s own place, and of saying goodbye. This evening also invites you to examine where you stand: Who is the theatre for, the old, the young or those in between? Are you satisfied with the roles you play in your own life? And what do you want to say goodbye to?

- Staging

- Christopher Rüping

- Stage design

- Jonathan Mertz

- Costume design

- Tutia Schaad

- Light

- Gerhard Patzelt

- Dramaturgy

- Moritz Frischkorn

- Audience Development

- Mathis Neuhaus

- Touring & International Relations

- Sonja Hildebrandt

- Artistic Mediation T&S

- Zora Maag

- Production Assistance

- Dominic Schibli

- Stage design assistance

- Karl Dietrich

- Costume design Assistance

- Renée Kraemer

- Production intern

- Anna Vankova

- Costume design intern

- Selma Jamal Aldin

- Dramaturgy assistant

- Lisa-Maria Liner

- Inspection

- Dayen Tuskan

- Soufflage

- Ursula Hildebrand / Katja Weppler / Gerlinde Uhlig-Vanet

- Surtitle installation

- Anne Hirth PANTHEA

- Surtitle translation

- Ambika Thompson PANTHEA

- Surtitel drivers

- Josephine Scheibe / Maya Scharf / Holly Werner / Aika Baumgartner

The translation by Thomas Brasch was partially adapted for Christopher Rüping's production.

Supported by Zürcher Kantonalbank & Else v. Sick Stiftung

In cooperation with LAS Art Foundation

Performance rights: Suhrkamp Verlag AG Berlin

Ad

Ad

About this production

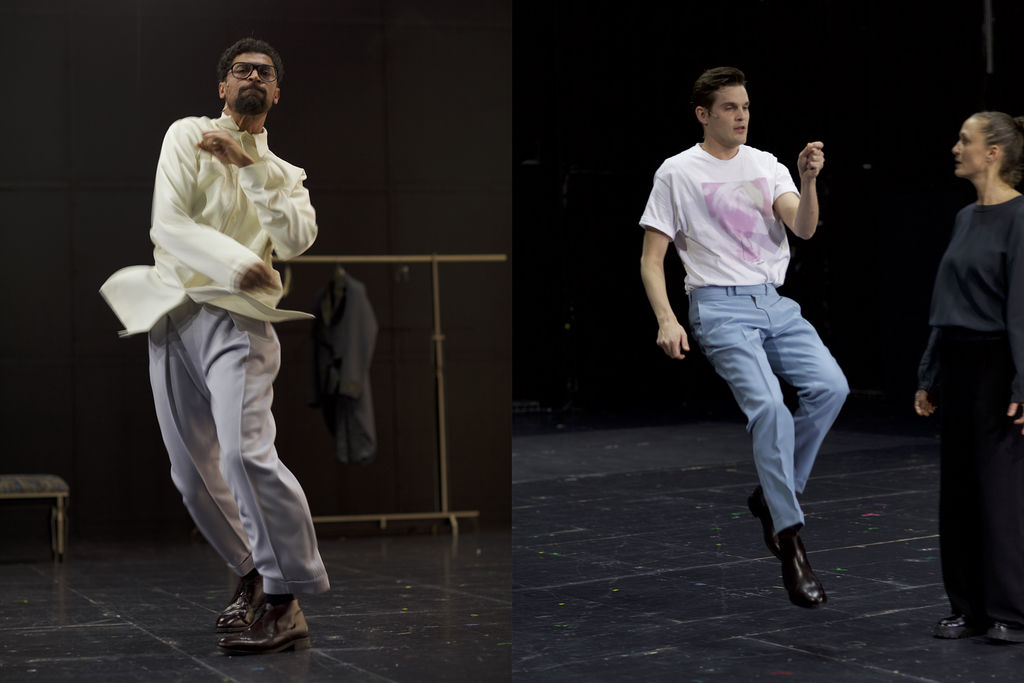

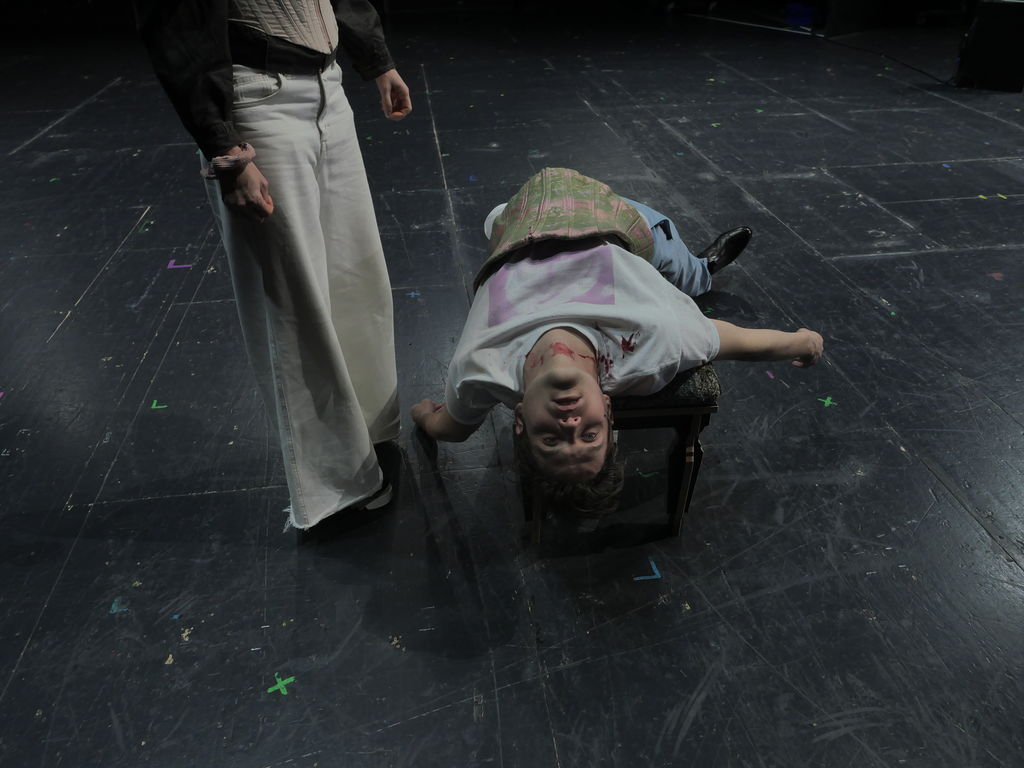

Seven people are sitting on a bench in an empty theatre space. They are waiting. Then they begin – to recite the play The Seagull by Anton Chekhov. First the title and the author's name are mentioned, the stage directions are quoted. Then the play begins. The seven people on stage are the performers Ann Ayano, Maja Beckmann, Moses Leo, Benjamin Lillie, Wiebke Mollenhauer, Lena Schwarz and Steven Sowah. They are making an attempt: they are playing that they are playing The Seagull. Or are they simply playing The Seagull? In any case, these people become more and more involved in the play, in this cosmos of self-ignition, rage for life, desire for art, unhappy love, and fear of their own disappearance. Although they resist, the seven performers are sucked into The Seagull. Can we follow them, will they return?

Anton Chekhov wrote his play The Seagull, the first of his great dramas, in 1895. At the time the play was completed, Chekhov was 35 years old and already a famous prose writer. He writes to his publisher Suworin on 21 November: “I have finished my play. I began it forte and ended it pianissimo – against all the rules of dramatic art. It has become a novella. I am more dissatisfied than satisfied, and when I read my newborn play, I once again come to the conclusion that I am absolutely not a playwright.” Long before this term was coined, Chekhov invented with The Seagull a form of proto-autobiographical theatre that is at the same time strongly linked to a reflection on theatre-making itself.

To begin with, it is interesting for our production that Chekhov reads himself into all the characters in his play. In fact, he seems to have an almost personal relationship with all the characters in his Seagull: The character of Masha – the punk girl of the play – bears the pet name of his sister, whom Chekhov talked out of her marriage wishes throughout her life. Nina – the young actress – is a picture puzzle of different lovers and friends of Chekhov, including references to real medallions and personal suffering. The older actress Arkadina is the prophetic prediction of his own marriage: in May 1901, Chekhov will marry the actress Olga Knipper, who will actually play this role in the famous second performance of The Seagull at the Moscow Art Theatre by the theatre theorist and director Konstantin Stanislavsky, but whom Chekhov did not even know when he wrote the play.

The degree of projection is even more evident in the play's male characters: the teacher Medvedenko can be read as the embodiment of Chekhov's own duty of care towards his mother and sister. Dorn is the fantasy image of his own ageing as a contented, admired doctor. (In our production, parts of Dorn's text are merged with the character of Medvedenko, played by Steven Sowah). The successful, established but inwardly insecure writer snob Trigorin repeatedly quotes from stories written by Chekhov himself and, again like Chekhov himself, loves fishing. And, the young artistic revolutionary Kostya is the embodiment of Chekhov's own desire for renewal in art and theatre. Perhaps, as an initial hypothesis, the play also invites us as theatre makers and you as spectators to take a position on trial: Which character do I identify with? Which character can I read myself into?

And yet, the play makes this sense of identification both difficult and easy at the same time, because all the parts are initially drawn as woodcut-like caricatures, from which three-dimensional figures emerge with whom we can empathise. Before The Seagull, Chekhov had mainly written farces, i.e. comedic one-act plays. But the author also labelled his full-length dramas as comedies, although today they are admired for their deep, meaningful portrayal of inner-psychological conflicts, depicting tragic entanglements and in several cases, including The Seagull, ending with the suicide of one of the main characters. At the end of the play, Trigorin then assesses Kostya's suicide, but also the play as a whole, as a “new genre, a case in between. Between tragedy and comedy.” In our case, we read the relationship between comedy and tragedy as one that shifts over the course of the evening: away from a distanced, cold view of the characters, towards understanding, identification, doom.

Chekhov succeeds in making the audience smile at his characters on the one hand, but also in evoking our compassion. The literary historian Elsbeth Wolffheim writes: “What characterises his plays as comedies is not the comedic exaggeration of Molière's or Shakespeare's comedies; rather, Chekhov defines the comic as the inappropriate. His dramatic characters are comic because they bypass reality, because they have a disturbed relationship to reality. It is precisely because of this that their emotions, actions and, above all, their omissions appear comical.” (Elsbeth Wolffheim, Anton Cechov, Rowohlt, 1982, p. 107 – translation SW) In The Seagull, Chekhov practises a thoroughly likeable form of malice, which consists of making fun of everyone and everything, especially his characters. Even the title is a parodic allusion to Ibsen's Wild Duck. The play within the play, which the young playwright Kostya is having performed, is an ironic formulation of a supposedly “Russian” symbolism. Above all, however, Chekhov parodies himself in the character of the privileged, egocentric Trigorin. Chekhov repeatedly shows the incongruence between his characters’ intentions and their actual actions. To the extent that the characters in The Seagull misjudge the reality of their lives, the play allows the audience to “see through this inconsistency and thereby distance themselves from the characters.” (Wolffheim, p. 107)

At the same time, there is an ethical offer behind this aesthetic process – that of role distance. Contrary to a conventional interpretation of Chekhov's dramas as atmospheric naturalism, his theatrical offer is thus more akin to that of Bertolt Brecht, but without being determined by his concrete political aims: Chekhov wants us to encounter his characters with distance, possibly to allow us to distance ourselves from our own lives. At least, as various biographies suggest, Chekhov, who had to live through a cruel childhood in poor circumstances, practised a strict form of continuous self-ironisation: “Chekhov’s endeavour to ridicule a seemingly unambiguous emotion through precise description, to equate the effect of tenderness with a peppermint drop, in other words to expose the inadequacy of feeling and reality, sometimes degenerates into an obsession. [...] The scepticism towards feelings that is, as it were, beaten into him is, of course, translated into misanthropy, but to the same extent it is counteracted by his sense of the comic, which makes him confident. So we have to differentiate: For Chekhov, the comic is on the one hand a kind of mimicry through which he camouflages himself from the outside world, and on the other hand it serves him as a defence against lies and hypocrisy.” (Wolffheim, p. 23) In his plays, he succeeds in filling this ironic distance with love. If we keep the process described above in mind – the author Chekhov reads himself into all the characters of The Seagull – and even understand it as an invitation, an ethical testing ground emerges in which strong moments of identification and distancing balance and complement each other: “My empathy,” the author and his play seem to say, “encompasses you all, but we don't need to take each other seriously because of it.”

The ethical offerings of Chekhov's dramas outlined here seem tailor-made for the staging strategies of director Christopher Rüping. He has been working for many years, often with the same actors, on a specific style of performance that was already alluded to at the very beginning of this text: The stage is not populated by specific characters, but rather the performers themselves are always present. They relate their performance to the real situation of the performance, i.e. the encounter with each other and with the audience. In the live situation of the performance, a process of rapprochement and empathy is then demonstrated: It is as if the performers are getting to know their characters in front of the audience in order to observe what reactions and emotions this encounter evokes in the audience.

In many respects, the methodology of this production corresponds to the content of the play. In both cases, we encounter a group of theatre makers who deal with the questions with each other and among themselves: Why theatre? Are we still carrying on and is it still worth it in the face of multiple crises? Who deserves a place here, who has to make room? Where do we position ourselves, as individuals, as a group, as an institution? Where did we stand in the past and how will our position change in 10, 20, 30 years? Seen through this lens, Chekhov's Seagull is more than just a generational conflict or the unhappy love affairs of its characters. The play offers us a structure of interrelated positions that function like an offer of possible self-positioning on trial. The production considers this fact by casting all the characters from the same, middle generation, although the structure of the play is strongly based on a juxtaposition of two generations. This means that all the performers have to overcome an equal distance to their characters (at least if you take conventional casts as a reference, in which Arkadina and Trigorin are often portrayed by significantly older performers than is the case in our production), while this distance also becomes a playful resource. What a gift, then, that we are allowed to witness this process of becoming a character live. On an analytical level, it becomes clear that the characters in The Seagull are almost as similar as they are different: They are all in search of recognition and intensity, and in doing so, they all revolve primarily around themselves. On an ethical level, however, the production continues the author's paradoxical impulse, which is characterised by distance and closeness at the same time: where the generations in The Seagull look at each other as harshly as possible, this production is characterised by an understanding view of both generations.

And there is another important aspect: as the artistic directorship of Benjamin von Blomberg and Nicolas Stemann at Schauspielhaus Zürich ends in summer 2024, this production also means a farewell for director Christopher Rüping, as well as for the performers who came to Zurich with him. On the one hand, his Seagullis permeated by the question of the transience of one's own actions. At the same time, it uses the empathic ironisation offered by Chekhov's play for multidimensional self-reflection:

The longer the play runs, the more the performers give up their distance to the characters in the play. In concrete terms, this means, among other things: In Act 1 and 2, the original text is spoken almost exclusively in the translation by Thomas Brasch, which in its hypotactic structure clearly marks Chekhov's drama as an artificial language. As the play progresses, however, it is increasingly permeated by a less artificial level of language, which Christopher Rüping developed and wrote himself in collaboration with the ensemble. The performers speak the text of the play in their own everyday language. This brings them closer to their characters, at times almost vanishing behind their silhouettes. The Seagull, its fable and its characters, become more and more a kind of doomed context from which the performers can no longer escape. This fateful context of entanglement in the subject matter is symbolised, among other things, by the luxurious costumes by costume designer Tutia Schaad, which the actors gradually put on.

On the other hand – and this is a complex, paradoxical process – the production increasingly allows itself its own access to the material over the course of the evening: the better the performers get to know their characters, the stronger their impulse to not simply accept their fate, but to think it through. Our production therefore also asks, at least implicitly, which aspects of the play – but also, beyond that, of our own performance, staging or institutional work – we can and want to leave behind. Without claiming to be able to really leave the play behind, it opens up a horizon for a different activity: Theatre beyond canonical material, beyond certain conventions, beyond patriarchal patterns of action that are to be performed again and again without their supposedly cathartic effect ever signifying real social progress. It is as if The Seagull (and its central story of a young woman who is taken advantage of and abandoned by an older, powerful man) has to be performed again so that we can say goodbye to certain aspects of this classic drama.

But a horizon can only be recognised against the backdrop of a backlight. And so, at the end of this production, another light emerges: that of the moon, in the scenographic interpretation of set designer Jonathan Mertz. What this moon signifies remains unexplained. Is it a sign of farewell, of the age of self-ignition and self-immolation and the unconditional will to art? Is it the tragic fulfilment of a fate inscribed in the play (namely that of Nina's character)? Or a third option? The question of who or what is said goodbye to, buried or abandoned in this Seagull must ultimately be answered by you. In order to pose this question pointedly, however, this attempt is necessary: Seven people are sitting on a bench in an empty theatre space. They are waiting. Then they begin to play that they are playing The Seagull. Or were they simply playing The Seagull?

Ad

Ad

AD

AD